Chip Carving with Amy Costello

On August 23rd, a group of students gather in the impeccably maintained workshop of accomplished woodworker, writer and teacher, Chris Gochnour, to learn the craft of traditional English chip carving from instructor Amy Costello. For a class of five students, Chris’s shop is, to make an understatement, more than adequate.

Should you ever earn the privilege of being invited to Chris’s shop you would see exactly how a shop should be kept. 30 years of trial, error and research have been dumped into the shop’s current iteration, and it shows. Walking into the shop, which is no smaller or bigger a space than a single woodworker needs to produce custom work, the lack of sawdust and clutter seems almost suspicious. Chris actively produces articles for Fine Woodworking Magazine where he is also an editor. He also works through designs and joinery methods for his class at Salt Lake Community College--and this is all on top of working one on one with his own personal clientele. For the level of cleanliness and organization in his shop, one would think all he does is hike the surrounding mountains with his wife and pup; it’s hard to imagine so much work actually goes on in the space.

Seven of us pile into Chris’s shop for three days to learn chip carving from the talented and driven woodworker Amy Costello. Amy first learned woodworking in the shop at BYU while completing a degree in Industrial Design. From the start, her learning curve seemed almost non-existent. Her first piece of furniture was a desk with two banks of cabinets that curve in the front. This is exceptional, being that most beginners usually work only in straight lines and square corners and struggle even at that. Working with curves requires a great deal of careful planning, building of jigs and accurate execution. Amy’s design prowess and craftsmanship have only improved since, especially as she developed an affinity for the turning of bowls on the lathe and for intricate chip carvings, skills which she often employs in a single piece. Not to mention that she now works almost exclusively in her bedroom at home on a platform about the size of a single piece of 4’ x 8’ plywood cordoned off by a tarp on a rope to keep most of the sawdust and shavings contained. In short, she’s a real badass.

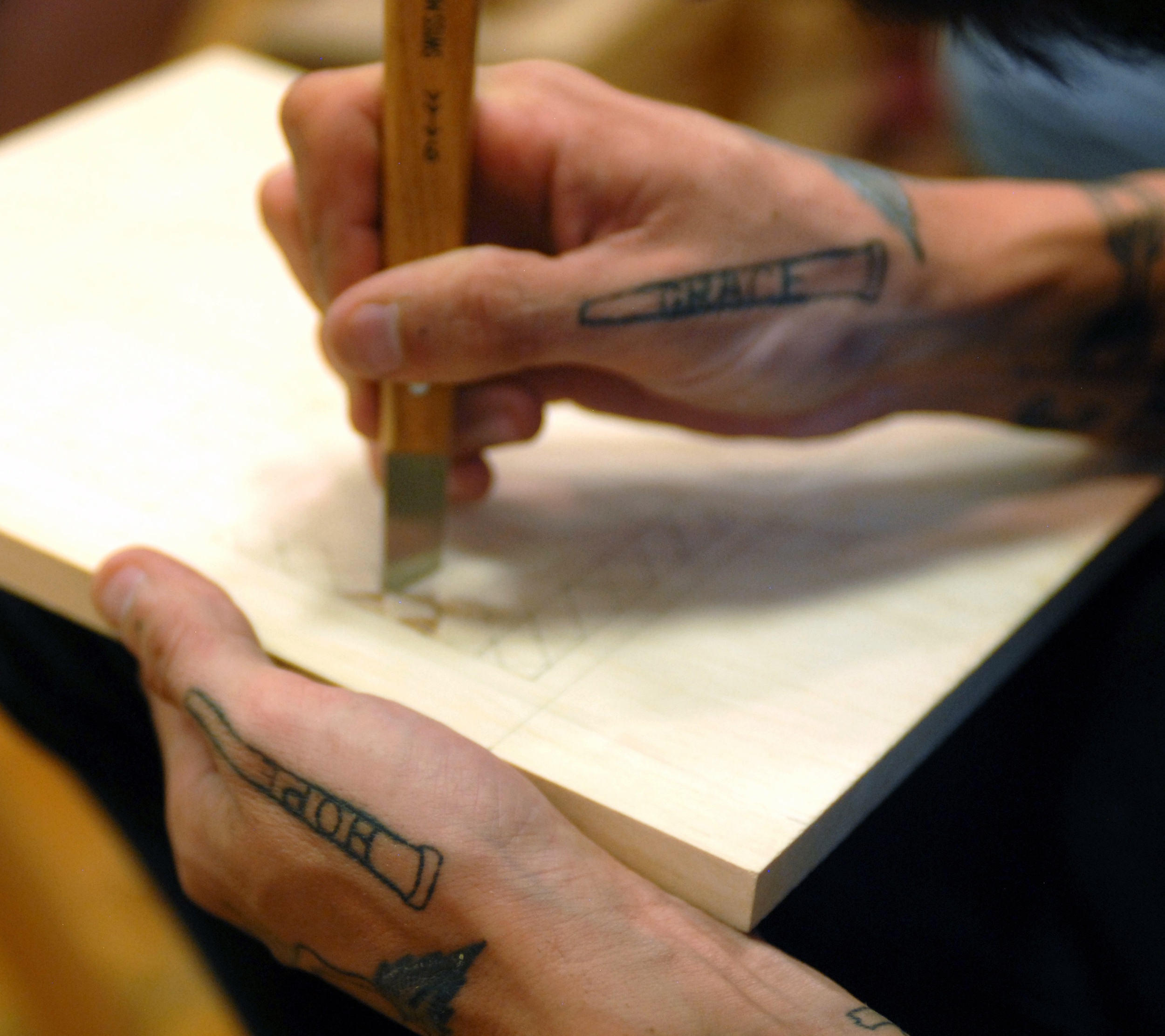

The class is organized around the creation of four different carving designs, laid out in 3-1/2” squares on a single board that will become drink coasters at the completion of the class. The first is a raised diamond pattern; the second, a Japanese “Asa No Ha”; the third is a seashell-like pattern; and the fourth is to be designed by the student. For the cost of tuition, $210, the students are supplied with two carving knives from Swiss hand tool maker, Pfeil (a dream of a company which still resides in Lagenthal, Switzerland where it was founded). Toolmaking was once a rite of passage for woodworkers, the tools which they made being the only ones they used. How could wood be worked without any knives or planes? 150 years later, this tradition has fallen by the way and been replaced by a large orange warehouse. I like to imagine as a woodworker, living and working in a centuries long tradition in the very place where that tradition started (alongside other places in the world simultaneously), making tools for other woodworkers around the world, no doubt finding time to take some shavings for yourself using a set of tools you made. This must be what is really meant by the phrase, “living the dream.”

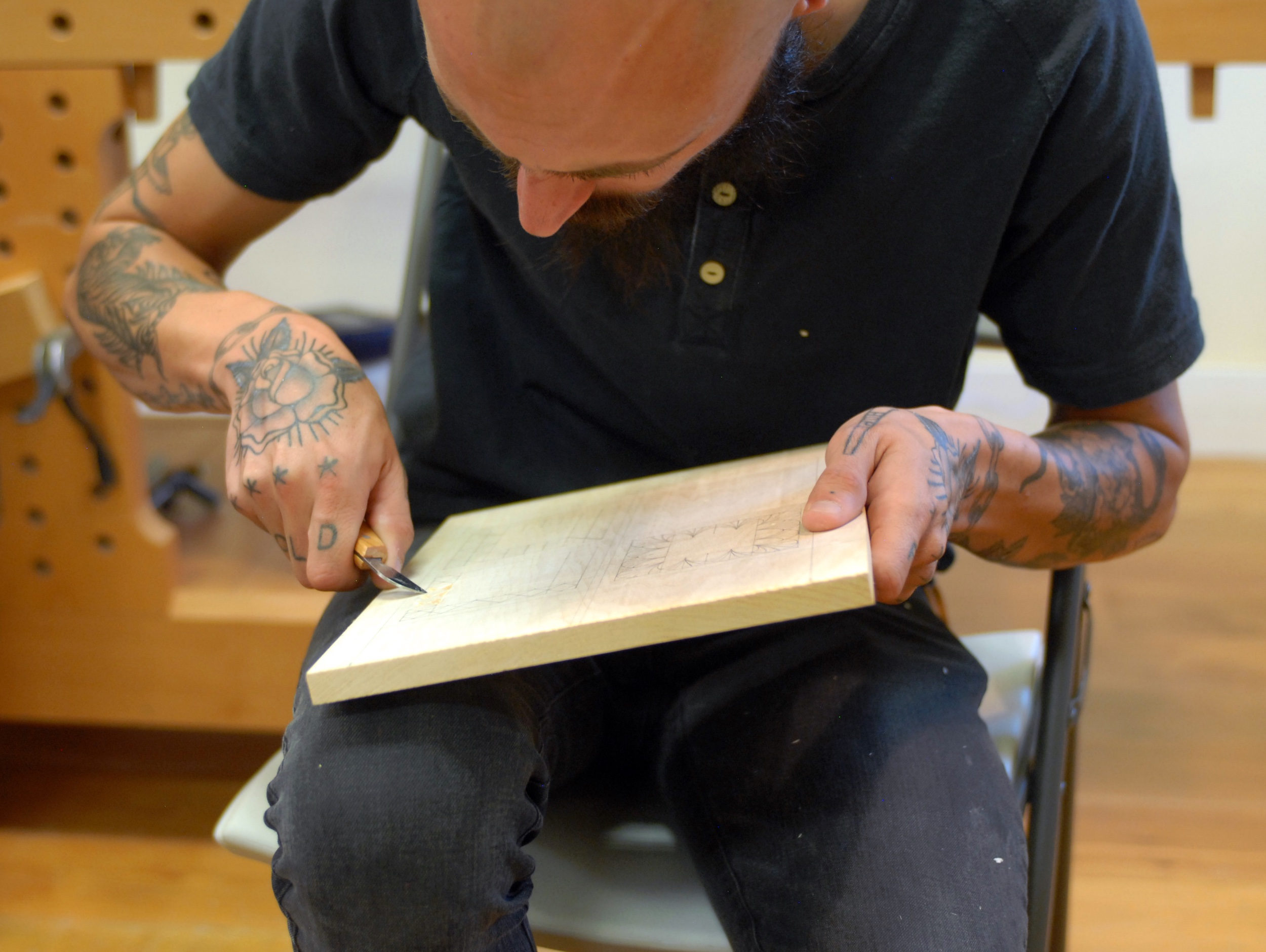

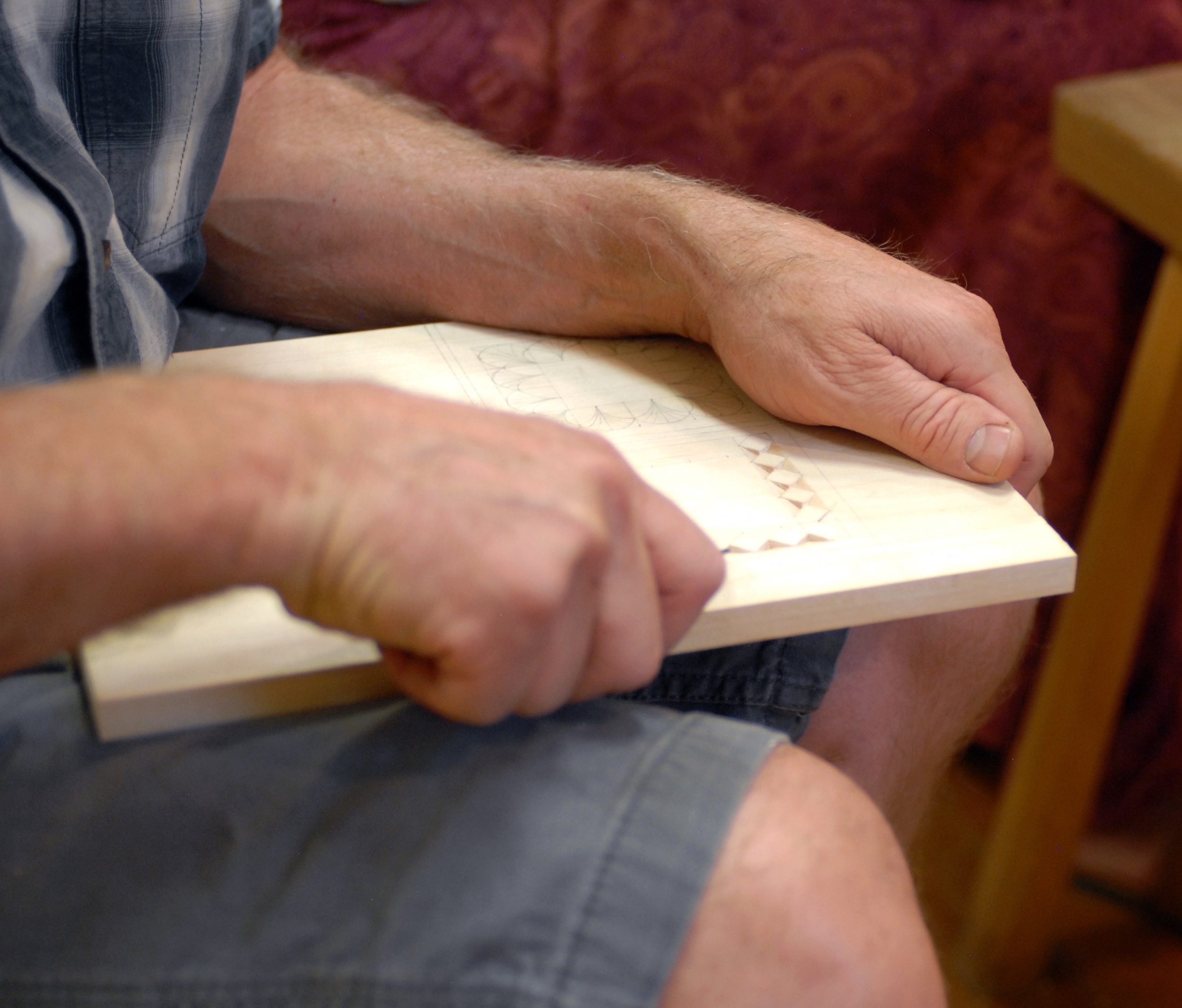

Students begin with the raised diamond pattern, learning the basics of how to hold the knife and position the body to make carving more comfortable and control the cuts. Amy prefers to be sitting feet up, knees bent, on the floor, couch or any place which lends itself to supporting the workpiece with the lap. Students begin hunched over in their chairs, and once their neck and/or back began to hurt, soon find themselves looking for places to put their feet up, bringing the torso and workpiece into a more comfortable, vertical position.

Once students feel comfortable using the tool, they can focus more on controlling the cuts. On the diamond pattern there are three cuts per facet and 43 facets per piece for a massive number of 129 cuts per piece. Yeah, it’s good to get comfortable before you start. If that count seems insurmountable to you, be aware that once the chips start cooperating with you and you get on a roll, it’s god damn difficult to stop carving. After about an hour of fumbling around with the tool, adjusting your grip, adjusting back to the way you had it before which didn’t work, adjusting it back again, cutting too far past your lines and massaging your hands which are for some reason incredibly sore, frustration begins to set in.

But then, the first chip pops out of the cut just right, leaving a perfect little diamond-shaped divot glistening up at you. The feeling that follows is one of intense personal satisfaction (instant gratification), and once you get good at the diamond pattern, you have 43 units of personal satisfaction (instant gratification) to look forward to. Be weary, gentle reader, that once you begin learning to chip carve, you don’t let it consume your life. Set limits on the time you spend carving and the money you drop on knives and basswood. Don’t let dreams of various carving patterns keep you up too late at night, and for Pete’s sake, don’t quit your day job!

I know the class is going well when on the second day I show up with lunch for everybody and not a soul looks up from their work. Twenty minutes pass before anybody reaches for a sandwich. (Shout out to Grove Market Deli on 19th South and Main, where a half sandwich is actually a whole sandwich and their whole sandwich is two, disguised under the price of a single sandwich.) Lunch with the class is one of my favorite parts because, well, food!, but also because of the chance to sit and enjoy a meal while discussing favorite tools, and I get to learn about the professions and lives of the other students. Good, wholesome fun.

At the end of the three days the coasters existed in various stages of completion (this is not an easy skill to learn), but a smile was plastered to the face of each student. Because chip carving requires nothing other than the knife and the workpiece, the student is able to take their knives and newly acquired skills home and continue to practice to their heart’s desire.

If this wordy article has piqued your interest in chip carving, we will be planning more classes in the future. Visit GoodCityCraft.com for more info. Cheers!